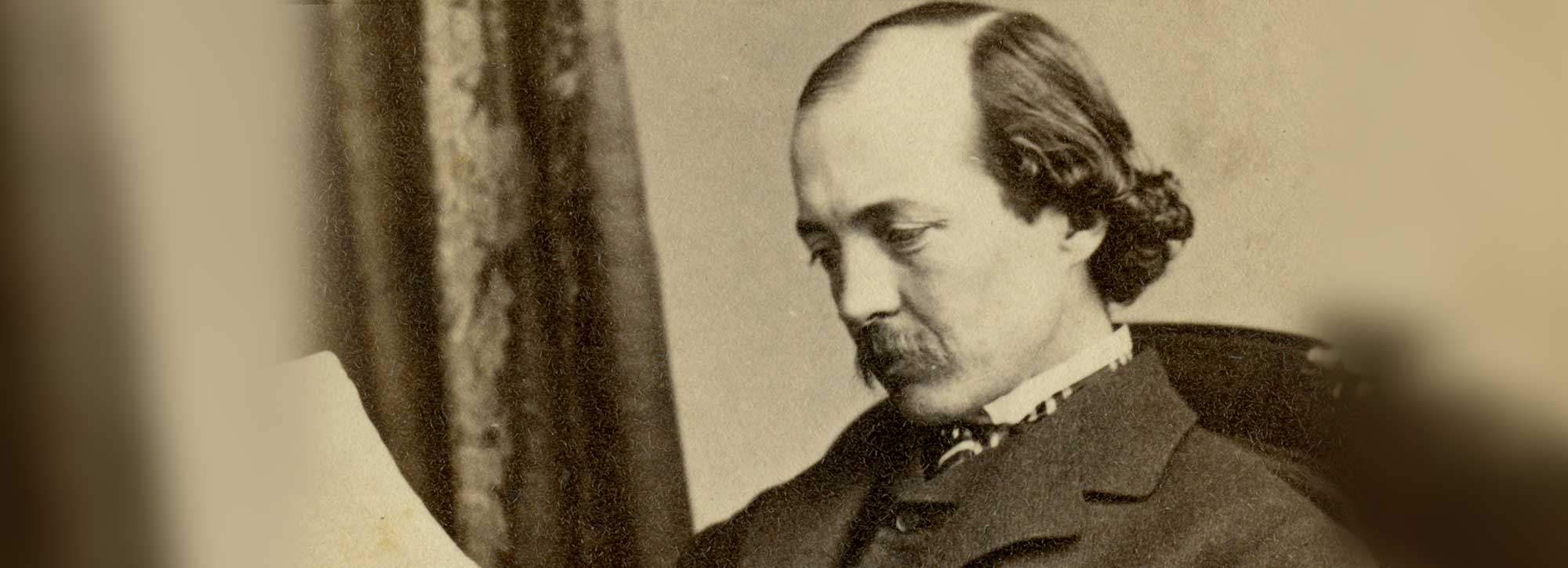

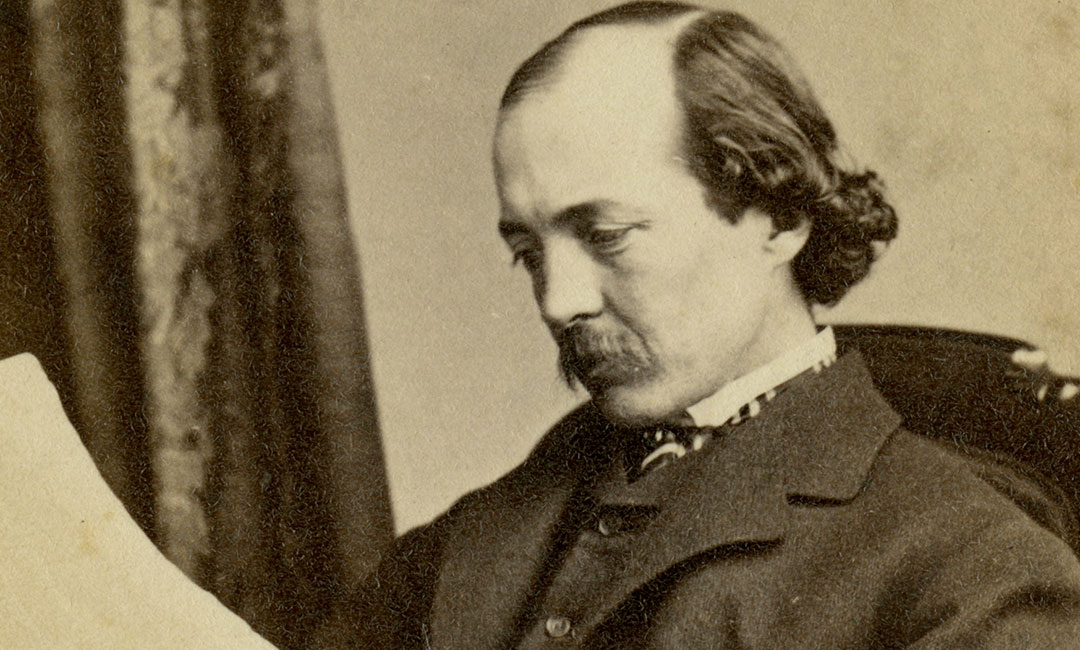

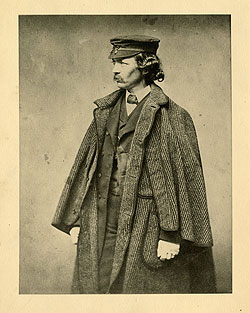

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 – 1903)

Frederick Law Olmsted was the leading landscape architect of the second half of the 19th century, and the architect of Lake Park in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Olmsted is perhaps best known for the design and creation of Central Park in New York and the U.S. Capitol grounds in Washington, D.C.

The design concepts employed by Olmsted and his partners have 15 elements in common:

1. They are man-made works of art.

2. They have their roots in the English Romantic style.

3. They reflect a Victorian influence.

4. They provide a strong contrast with the city.

5. They are characterized by the use of bold landforms.

6. They provide a balance between turf, wood and water.

7. They use vistas as an aesthetic organizing element.

8. They contain a series of planned sequential experiences.

9. They provide for the separation of traffic.

10. They provide visitor services.

11. They contain artistically composed plantings.

12. They integrate the architecture into the landscape.

13. Each has provision for a formal element.

14. They are characterized by variety.

15. They are built to provide for recreation.

More on the Life of Frederick Law Olmsted

By Margarete R. Harvey, ASLA

Frederick Law Olmsted (F. L. Olmsted) was the leading landscape architect of the second half of the 19th century well before there was any established curriculum or training program for landscape architects, or a professional organization in the field such as the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). He is acknowledged as the father of American landscape architecture even though he was preceded by highly respected practitioners. He also had some very strong competition from landscape architects working at the same time, who are largely forgotten today.

Despite these distinguished colleagues, Olmsted is considered the father because his firm dominated the profession until at least 1920. With his first partner, Calvert Vaux, he designed and supervised the creation of Central Park in New York (1858-1863, 1865-1878), Prospect Park in Brooklyn, parks in Buffalo and Chicago, and the residential community of Riverside, Illinois. Together, with other partners and staff, Olmsted’s office carried out some 550 other commissions before his retirement in 1895. The most important ones are: Mount Royal Park in Montreal, Belle Island Park in Detroit, the U.S. Capitol grounds, Stanford University campus, park systems in Boston, Rochester and Louisville, and his two last great projects: the World’s Columbian Exposition (1888-93) and Biltmore, the Vanderbilt estate in Asheville, North Carolina (1888-95).

His stepson, John Charles Olmsted, and his son, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., carried on the Olmsted firm. They oversaw some 3000 new projects between 1895 and 1950. And, a majority of influential landscape architects were apprenticed or worked in the Olmsted firm in Brookline, Massachusetts carrying the Olmsted design philosophy.

In 1980, the National Park Service bought the home and office of the Olmsted firm in Brookline, Massachusetts to create the Olmsted National Historic Site. Many of Olmsted’s plans and drawings are preserved and available for purchase there.

Well, how did this all happen to the scion of a well-to-do dry-goods merchant in Hartford, Connecticut? Frederick’s early life was guided by a doting father – his mother had died when he was 3 years old, shortly after the birth of his younger brother, John Hull. His father took his family on numerous excursions to view scenic landscapes and experience the spiritual “uplift” it provided. By the time he was twelve, young Frederick had seen most of New England, Niagara Falls and Quebec. He was a dedicated to the picturesque, as was his father. On one occasion, he and his brother, then 9 and 6 years old, respectively, hiked 16 miles through unfamiliar country to visit an aunt and uncle. It took them two days and an overnight stay at an inn – inconceivable today.

But, his schooling was erratic. He was sent to his first boarding school at the age of 6. By the time he would have finished the equivalent of high school, he had been in 12 different programs. Yet, he was curious and had a natural love of learning. He contracted sumac poisoning which threatened his eyesight and eventually kept him from entering Yale. Instead, he embarked on a series of apprenticeships, in turn, intending to become a surveyor, a merchant and a farmer – careers that were all for naught.

In 1842, when his brother entered Yale, Olmsted became an apprentice seaman. Since he was of slight build and afflicted by seasickness, he experienced a misery he could not have imagined and never forgot the brutalization and injustices of seafaring life. Once back in the U.S., he wrote numerous letters to New York newspapers urging changes in maritime law to protect seamen and passengers alike.

This was to establish a pattern: Olmsted would undertake a new venture, a new career or a journey, reflect, and then write about it under the pen name “Yeoman” which symbolized to him the ideal democratic citizen who exercises his rights and responsibilities to himself, his family and his community.

In turn, he became a “scientific farmer”, with his father buying him two different farms. He beautified his farms, yet never made money on them, but he learned about good drainage and good soil preparation. He went on a walking tour of England, followed by a month of traveling throughout Europe. From then on, he would always take pleasure in travel and in recording his observations of places and people – a necessary prerequisite if you consider the extent of his travels criss-crossing the North American continent at a time when the railways were being constructed and well before any automobiles or aeroplanes. In fact, he used all modes of transportation of the times: riverboat, rail, carriage, horseback and foot.

In England, he fell in love with the visual richness of the English rural landscape, the factors of which would serve as principles of design for his parks, campuses and suburban developments later on. He commented:

“The great beauty and peculiarity of the English landscape is to be found in the frequent long, graceful lines of deep green hedges and hedge-row timber, crossing hill, valley and plain, in every direction, and in the occasional large trees dotting the broad fields, either singly or in small groups, left to their natural open growth … therefore branching low and spreading wide, and more beautiful than we often allow our trees to make themselves.”

But, in particular, he discovered the newly created Birkenhead Park, a pioneering public project that transformed 125 acres of farmland across the Mersey River into an oasis of nature available to all citizens of crowded, industrial Liverpool. He wrote:

“Five minutes of admiration, and a few more spent studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty, and I was ready to admit that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable to this People’s Garden.”

Here, Olmsted began to envision the possibility of shaping and tending the earth not only for its agricultural benefits and scenic potential, but also for the betterment of society. Olmsted reckoned that planned parks – or what was later to be called landscape architecture – could be used to promote civility and to encourage communicativeness (across class barriers) and could be characterized as the driving force behind the genius of civilization.

His book “Walks and Talks”, about his travels in England, benefited from his gift for observation, reflection and clarification. So did his writing about his travels in the United States between 1852-54, which show his rhapsodic response to American scenery.

Olmsted held sturdy opinions about political and social matters. He made a point of being well informed and of informing others of his opinions on such matters as slavery, urban design, conservation of forests, education and civilization. In his book “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States”, he challenged virtually every attitude about slavery which he contended made barbarians out of slaveholders.

In Texas, he found the German settlement of New Braunfels, near San Antonio, which he considered an oasis of civilization. It was a community based on free labor and therefore free of the brutality bred by slavery. Olmsted made friends among the Texas Germans, he admired their community life, the importance they placed on home, education, independence and hard work, and the level of education they maintained through reading, music and conversation. He kept in touch with them through letters …. which were still talked about in 1994 when the ASLA held its annual conference in San Antonio.

The publication of his journals and books made him see himself as a man of letters and ideas. As New York’s literary society opened its doors to him, he hoped to finally becoming a self-supporting man – of substance! He yearned to be recognized as a leader in society and to contribute to society’s improvement. Again, with substantial capital from his father, he became a partner in a publishing firm (Dix and Edwards). This brought him into contact with such writers as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadworths Longfellow and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Yet his venture too was doomed and by 1857, the firm was irretrievably on the road to financial ruin.

Olmsted was humiliated by the failure of the publishing house, unable to repay his loans, and without hope of another project. His farm, on Staten Island, was floundering, and his beloved brother, who ran the farm for him, was dying of tuberculosis. Olmsted retreated to the coast of Connecticut to rest and ponder his future. This was another pattern throughout his later life: problems, controversy, overwork and eventual retreat to nature.

Then, in August 1857, came the opportunity that changed his life when the 35 year old Olmsted met Charles Elliot at a local inn. Elliot was one of the commissioners for the central park to be created in New York. He suggested that Olmsted apply for the job of supervisor of the park that Andrew Jackson Downing and William Cullen Bryant had been advocating for years.

The Central Park project finally gave Olmsted the laboratory he needed to test his evolving theories about civilization, urbanization and leadership. Despite his lack of formal education, he had the right set of skills for the undertaking. He knew surveying, understood topography and mapping; he knew the rudiments of agriculture, the value of good drainage and soil preparation and the need for good management of his workers. He had developed aesthetic standards for scenic beauty and a strong political belief in the importance of public parks in providing recreation and spiritual renewal in settings of natural beauty for all classes of people. He had honed his talents for communication, clear thinking and writing and, finally, he had shaped his attitudes about the humane exercise of power and leadership. After considerable politicking and self-promotion, Olmsted was hired.

When Calvert Vaux, the young architect whom Downing had brought over from England, asked Olmsted to collaborate on a submission to the competition for the design of Central Park, Olmsted learned the techniques and fundamentals of design from him. Their brilliant design, called the Greensward Plan, won the competition.

The design provided long pastoral passages intended to give the repose of the rural landscape to the urban population, to promote strolling and meditation in picturesque dells, vistas atop dramatic outcroppings of rock “where you take in all this magical landscape without moving” and sequential mysteries. Sheltered from the jostle of the city streets, the visitor might walk, ride on horseback or enjoy a leisurely carriage ride around the park and move around without the danger of collision, because the designers kept all these functions separate throughout a series of over and under-passes – particularly important for today’s cross park traffic.

The partnership of Olmsted and Vaux was launched on the road to the success story I related at the beginning of my presentation. It was not all plain sailing, however. The construction of Central Park was the largest public works program of the time. There were rivalries between the partners. Vaux felt relegated to second place. There were political pressures and conflicts with the engineer/surveyor and the financial controller. Again and again, Olmsted would use his connection in the newspaper world to expose and overcome them. There were interruptions due to overwork and exhaustion from managing their 2000 men workforce, when Olmsted would retreat to the Connecticut coast for recuperation, and there was the serious break when Olmsted resigned during the Civil War to become the first head of the Sanitary Commission, from which he was later fired.

Thereafter, driven by the need to provide for his family of five – Olmsted had married the widow of his younger brother John and adopted his 3 children in 1859 – he worked for a California gold mine, the Mariposa Company. When the mine was foundering, Olmsted returned to work with Vaux until the completion of Central Park (1865-1878). Finally, at the age of 42, Frederick Law Olmsted was to embark on the most productive years of his life and Central Park was to be the crowning glory of his work as a landscape architect.

In addition to all the ensuing commissions for park development all across the continent, Olmsted was anxious to preserve areas of great natural beauty for public enjoyment. He served as head of the first commission in charge of the Yosemite Valley and was a leader in establishing the Niagara Reservation – the forerunners of the National Park system. And although he drew heavily from English traditions, he recognized the importance of developing distinctive landscape styles suited to the conditions of the area; thus by beginning to develop water conserving landscaping styles appropriate to the semi-arid climate of the American West, he foreshadowed the importance of environmental forces in landscape architectural design. Lastly, Olmsted sought to launch a landscape design profession that rejected mere decoration, in order to create outdoor spaces that met the social and psychological needs of Americans in a comprehensive and imaginative manner, for which we can all be grateful.

Literature:

Ralph M. Aderman (Ed.). Trading Post to Metropolis, Milwaukee County’s First 150 Years. Milwaukee County Historical Society, 1987.

Lee Hall. 0lmsted’s America, An “Unpractical” Man and his Vision of Civilization. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1995.

Bruce Kelly, Gail Travis Guillet & Mary Ellen W. Hern. The Art of the Olmsted Landscape, New York: New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and the Arts Publisher, Inc., 1981.

Henry Hope Reed & Sophia Duckworth. Central Park, A History and a Guide. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1967.

William H. Tishler (Ed.). American Landscape Architecture, Designers and Places. The Preservation Press, 1989.